In the minds of most journalists, all human history can be summed up with the words, “Rome fell, then Hitler came.” A few more accomplished scholars among the chattering classes might be able to distinguish between the fall of Rome’s republic, followed by the empire, and the fall of the empire, followed by a thousand years of hideously faith-infused darkness. But basically, to journalists, all signs of political or cultural decadence — whether it’s a Republican being elected or some other Republican being elected — are omens that American Rome is about to collapse followed by the rise of American Hitler.

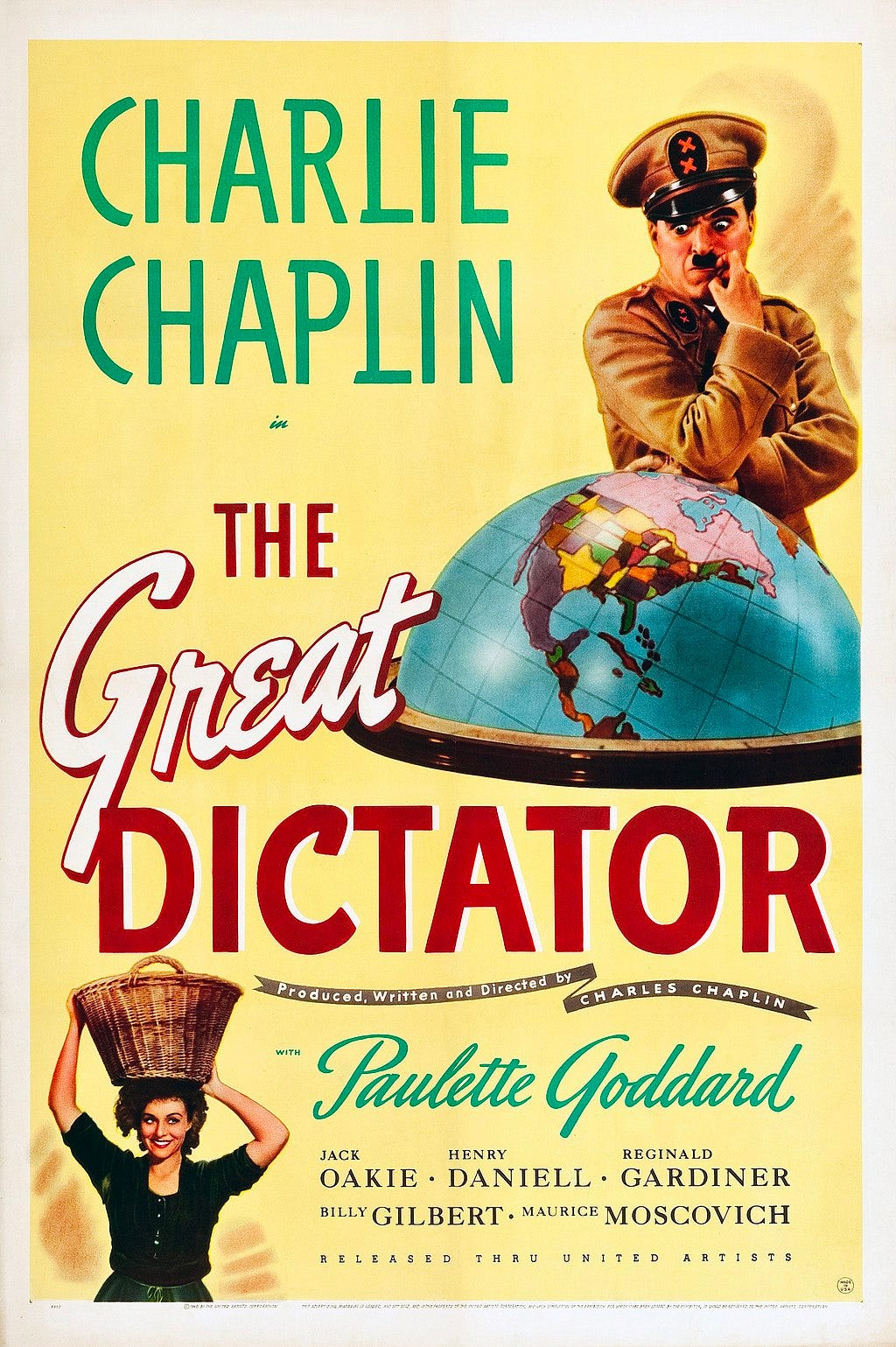

“A Confessing Church for America’s Weimar Moment,” reads a headline in The Dispatch. “We must not let the shooting of Charlie Kirk become Trump’s Reichstag fire,” writes a genius at The Guardian. “Welcome to Weimar 2.0,” headlines a book excerpt by the catastrophist Robert D. Kaplan in Foreign Policy. And that’s not even counting the continual Hitler forecasts on cable TV. One could almost feel sorry for der old Fuhrer, his psycho ass getting dragged out of hell every ten minutes to serve as a warning to us all.

And look, yes, it’s true, the United States is in one of those periods of dissolution and transition that come upon every nation from time to time. So too was Weimar, the unstable republic that rose up in the wake of Germany’s crushing defeat in World War I. Such periods are often marked by polarized politics, destructive sexual profligacy wrongly celebrated as liberation, and art forms informed by and infused with the general cultural decay. So with America. So with Weimar.

Beyond that, however, the comparison is a shallow one. For one thing, the image of Weimar among our clerisy is skewed with bias. Watch any movie set in the era — the musical Cabaret is a good one — or any television series — Babylon Berlin is my favorite — or read histories like Peter Gay’s famous Weimar Culture. You’ll get the sense that you’re learning about a time of delightful but doomed sexual and artistic creativity, with benign but hapless socialists slowly falling beneath the darkening Nazi shadow.

But no. The undisciplined sex lives, the anti-freedom politics of both the left and the right, and the shocking but ultimately ephemeral cultural productions were all one thing, all part of the same process of decay. Weimar — and the world wars that preceded and followed it — marked the end of a civilization — the greatest civilization that has yet existed on planet Earth — the civilization that was Europe from around 1345 to 1914. It was this, in fact, that gave Hitler his rhetorical super power: he diagnosed the decadence correctly. He just didn’t realize he was its ultimate manifestation. Ah well. Even a mass murdering racist lunatic can’t be right all the time.

So the U.S. is in a decadent state and so was Weimar, and decadence anywhere looks like decadence everywhere. History does repeat itself.

But it repeats itself for a reason. It’s the same reason a person’s life tends to repeat itself. The human race, like each of its individual members, has a nature, a character. Like everything that exists, character is bounded by its defining limits. Those limits cause it to express itself in a finite number of patterns. Over time, those patterns are certain to reassert themselves in recognizable forms.

The patterns of a healthy society or person will be shaped something like a rising spiral. Certain arcs of activity will recur over and over, but they will recur in increasingly wise, creative and productive ways. There will be periods of dissolution but they will be what is sometimes referred to as “chaos leading to a higher plane.” You can trace such a pattern in the plays of William Shakespeare. You can find it in the history of England between Elizabeth and the end of World War II.

The history of a rotten society or person will form a descending spiral, the repeated arcs of foolishness and evil growing ever darker and more self-destructive. The life of every tyranny is like this. The life of every addict too.

Then there’s the history of an ignorant or neurotic society or person. This will simply look like a circle. The subject goes round and round on a level track while uttering occasional gasps of wonder at having found themselves at a place they’ve passed a hundred times before but have a hundred times forgotten. You know people like this. Every now and then, they announce they’ve had some smack-the-forehead revelation that will change their lives forever. Then they return to the exact same ideas and behaviors they’ve had before. Perpetually primitive tribes are also like this, no matter how we want to romanticize them.

In short, times of dissolution will indeed be followed by a transition. But Hitler — get ready for it — is not the only possible outcome. The time surrounding the French Revolution in Great Britain showed many of the usual signs of decadence, but the Victorian era that followed was arguably Britain’s greatest age. So with the U.S. in the 1920’s and 30’s. Those decadent days led to the mighty 1950’s and a new American half century. As with each individual, what follows a nation’s dissolution all depends on the essential health of the nation’s character.

Where then are we?

It seems obvious to me that the primary cause of our current decline is the falling away of the Baby Boomers. My age cohort has dominated the political and cultural landscape for seventy years. Now, we’re played out and heading for the exits. Our accomplishments were many. We made hypocritical virtue signaling an art, introduced self-destructive drug use to the general population, slowed the rise of black Americans by burying them under the smothering dependencies of the Great Society, and wasted all the money accumulated by every generation before us along with some money that will be accumulated by the generations to come. We also popularized the personal computer so, like, yay for us.

What the U.S. will become when we are gone is, of course, not yet clear, but it’s a good bet it will be defined by the way we use the new forms of communication that have been and are still being generated by technology. Who or what will dominate those engines of culture is largely what all the current division, panic, bullying and violence is intended to decide.

Periods like this are often resolved by the rise of a powerful personality. Will this person shape the coming Zeitgeist or merely ride its wave? Your answer will depend on whether you agree with Thomas Carlyle that “the History of the world is but the Biography of great men,” or with Tolstoy who said, “great men—so called—are but the labels that serve to give a name to an event.” Like the question of nurture or nature, this question is impossible to resolve, probably because, like the question of nature and nurture, the binary itself is an illusion. But as I say, contra the journalists, Hitler is not the only model for such era-defining personalities. George Washington and Queen Victoria are far more benign examples of the breed. Luther and Napoleon were mixed blessings. History is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re going to get.

When we scan the horizon for the coming definitive personality, it’s pretty hard to see the horizon with the gigantic Donald Trump standing in the way. So yeah, maybe he’s the guy. He has no coherent ideology so his effect may not be a lasting one. But he does bear all the marks of a Tolstoyan Godzilla. Like that monster created by nuclear blasts, Trump is the product of our generation’s eruption of materialist vulgarity. But he is also the avatar of the American everyman in our time. Like that character — much maligned by the elites who feed off his bounty — he is blunt, common sensical, creative, independent and bold. If he uses these traits to blast away such fatal nonsense as open borders, transgenderism and socialism — if he restores our simple patriotism and can-do spirit — the imprint of his nature may well be Trump’s legacy to the new age.

But this is still America. Perhaps the great figure that will shape our 21st Century is not Trump or any other individual, but we, the people. In that case, Weimar, with its sexual libertinism, its artistic DaDaism and its polarized politics, actually does serve as a guide — a guide to what each and every one of us should not do.

Let we, the people, then, like healthy men with healthy minds, eschew the habits of decadence.

Get your sex life in order. Give up porn and feminism and other such perversions, and yoke your desires to their natural purposes: the creation of families, the solidifying of marriages and the maintenance of self-governing homes.

In politics, murder your isms. Follow the facts instead. Do what works, what keeps people free, what makes free people happy, what encourages the wealthy but protects the poor. Our founding principles are still the best guides ever invented to achieving those ends. Use them. Make our leaders use them too.

And in the culture, forget the overrated shock of the new. In the arts as in life, follow one rule: Make something beautiful. Whether it’s a movie or an invention, a business or a family, a community at peace or simply a life lived lovingly and well. Turn your back on every ugliness and cruelty. Head down the path of beauty and, like the prodigal son, you will see your Father running to greet you from afar.

And that’s another thing — one last thing — love the Lord your God with all your heart and mind. In general, they neglected to do that in Weimar and ended up worshipping the devil instead. No matter what anyone tells you, those are the only two choices. Choose right, and I guarantee you, Hitler will stay in hell — or on cable TV, which amounts to the same thing — where he belongs.